Dream of the Red Chamber (Part One)

INTRODUCTION

Dream of the Red Chamber, also known as A Dream of Red Mansions, or The Story of the Stone, originally published in 1797 and written primarily by Cao Xueqin, is the most recent, and therefore most modern of the Four Classic Chinese Novels, a list that also includes: Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a military novel about a fractious period of China’s history and the heroes that emerged from it; Bandits of the Water Margin, also known as Outlaws of the Marsh, or All Men are Brothers, a story of 108 outlaws who band together to fight a despotic government; and Journey to the West, a mythological account of a Buddhist monk’s trip to India, accompanied by a mischievous monkey, a drunk and violent pig, and a loyal ogre-man. Of these four, probably Journey to the West and Romance of the Three Kingdoms are the most well-known among the youthful element of the English-speaking world, with Journey to the West serving as the inspiration for the popular manga/anime series Dragonball, and Romance of the Three Kingdoms spawning several television series as well as a whole plethora of video games, from hardcore strategy, to action games, to mobile slot machines. Bandits of the Water Margin may also be known to video game players as the inspiration for the series of role-playing games Suikoden, which is the Japanese name for the novel.

Dream of the Red Chamber is the most grounded and realistic of these four novels, with its supernatural elements serving mostly as a framework for a more mundane story. Its focus on the everyday rather than the extravagant and fantastical might explain its relative lack of popularity in the West, and its lack of anime or video game adaptations. There’s also the fact that it is steeped in the rituals and customs of Chinese culture in the 18th century, full of events and relationships that might immediately feel unfamiliar to the Western reader. However, I believe that the modern reader will find that this book, of the four, most closely resembles what they might think of as a novel, and, in my eyes, is actually the most approachable of the four, even if many aspects of its setting and structure may be unfamiliar or mysterious. In my biew, this novel is severely underlooked, and definitely belongs in the upper echelon of the World’s Great Works of Literature.

Readers coming at the book from a Western perspective will find that it doesn’t quite feel like anything they know. Some of this is due to the fact that it is coming from quite a different tradition, and its structural elements are tied to the form of the Chinese novel. However, even within this form, Cao Xueqin plays with the reader’s expectations, not giving us exactly what we want, and deliberately contrasting the realism of this novel with the operas and romances that the characters within are watching and reading. This is a work that concerns itself with real-life people: not mythological or legendary heroes; nor symbolic representations; nor shallow or vulgar caricatures. Most everyone in the book has a lot going on, and are often trying to balance their personal characteristics with their formal role and the expectations that come with it. In many ways, we could say that one of the primary ideas of the novel is this contrast between form and the reality that lies beneath.

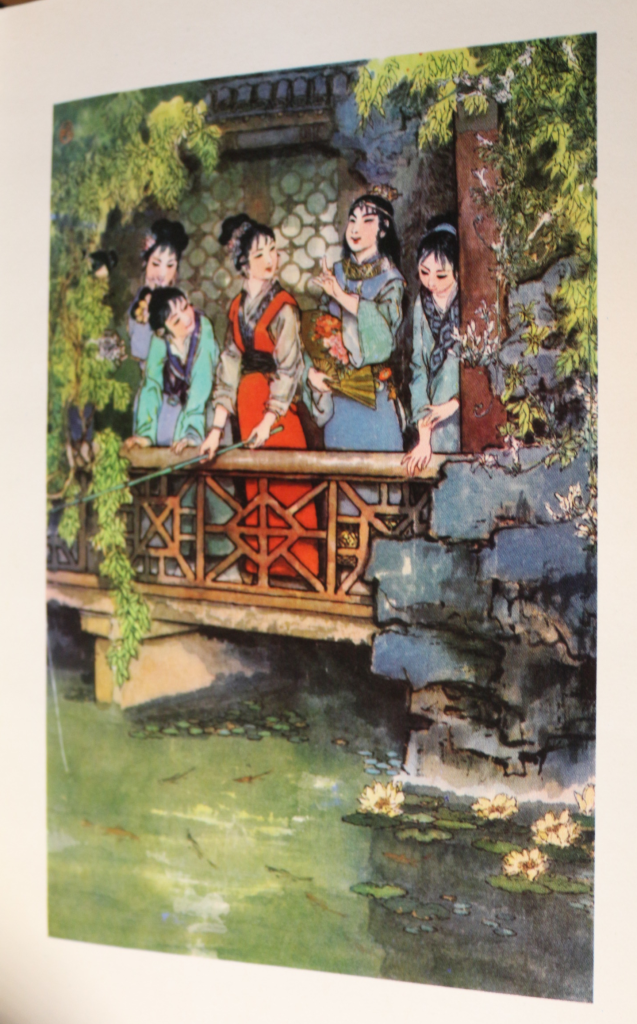

The book follows the Jia family, a so-called Grand Family with Imperial Connections residing in the city of Jinling, now known as Nanjing, and then the Capital of China. The Jia family is split into two houses who live across the street from each other in the Rong and Ning mansions. Our story focuses primarily on the inhabitants of the Jung mansion, which consists of three generations, the eldest represented only by the Lady Dowager, who occupies the highest point of honour in the household. The third generation, her grandchildren, grandnieces and grandnephews, as well as a few characters whose position in the family tree are too complicated to reckon with at the moment, are who we spend most of our time with.

The Jia family is an aristocratic and noble one. They are certainly well-off, but their status is based less on their wealth as it is on their connection to the Imperial Family and the honour that comes with it. A key signifier of their status is the fact that one of the daughters has been selected as an Imperial Consort, which is about as honourable position as a young woman can get. However, their financial position is slightly more precarious than it might seem on the surface, with much of their wealth being siphoned off into the elaborate ceremonies and gifts required to maintain their position, as well as being misused carelessly by the less responsible members of the family.

Only a few members of the household truly understand this situation, with the rest living in what is essentially a fantasy land. With each generation, their understanding of economy decreases, with more and more of the men of the family in particular devoting themselves entirely to book-learning, religion, or womanizing. The fact that their needs are taken care of almost automatically, and even their whims are fulfilled with ease, means that they are trapped in a perpetual childhood that points to the looming demise of the family.

In the first volume, consisting of chapters 1 through 40, which is the section of the book I will be focusing on in this first part, this fall is only explicitly indicated once, at the very beginning, during a conversation between two characters from far away. Once we actually find ourselves in the mansion, this grim fate exists only as a shadow in our minds, as no one caught up in this luxurious environment ever stops to give it any thought. Thus, even in the setting of the novel, we already see this contrast between appearance and what lies underneath.

For all this, the first volume does not seem to introduce the reader to much of an overarching plot. Aside from the introductory frame-story, we are mostly simply carried along through the everyday lives of the inhabitants of the mansion, primarily through following the youngest son of the main family, Baoyu, as he plays around with his sisters and cousins, and pays visits to his parents, aunts and uncles, and grandmother. Over the course of these forty chapters, a series of domestically significant but never earth-shattering events elucidate for us the personalities and relationships that exist within the mansion. While at the end of these 600 pages you might be hard-pressed to find much that has significantly changed in the world of the book, what you will find is that you, as the reader, have become a member of a large and complicated family; become familiar with some of their customs and traditions; and most importantly, find yourself eager to know what they might get up to later.

A term, originally coined in the world of anime and manga, but now often used to describe all sorts of media, is slice-of-life, and Dream of Red Mansions certainly fits this descriptor. The most important attributes of a slice-of-life work of fiction are that the setting and the characters feel real, and that the pacing allows one to become comfortable in this world and with these people. Instead of grand, dramatic events that shake everything up before you even know where you are, a slice-of-life story is more concerned with mundane events that shed light on the characters and their relationships. It is easiest to understand and appreciate Dream of the Red Chamber when placed within this sort of dramatic framework.

In terms of narrative structure, Dream of Red Mansions follows the tradition from Chinese novels when it comes to its chapters. Each chapter’s title contains vague descriptions of two events that often book-end the chapter. For example, the first chapter of Dream of Red Mansions is titled, “Zhen Shih-yin in a Dream sees the Jade of Spiritual Understanding/ Jia Yu-tsun in His Obscurity is Charmed by a Maid.” Later, we see such titles as, “An Eloquent Maid Offers Earnest Advice One Fine Night / A Sweet Girl Shows Deep Feeling One Quiet Day,” and “An Ill-Fated Girl Meets an Ill-Fated Man / A Confounded Monk Ends a Confounded Case.”

These playful titles are amusing, and also a great way to interest the reader in continuing the story. They make it clear that something new is going to occur in the near future, but what exact form this new thing is going to take is left up to the imagination. You begin each chapter with a little mystery: what earnest advice will this eloquent maid offer? Who is this ill-fated man? The only way to answer these questions is to read on, which is exactly what the author prompts us to do by ending each chapter on an often comically minor cliffhanger, and the statement, “To find out what happens next, read on.”

This is not groundbreaking by any means, and obviously we see this sort of device used in all sorts of serialized works. However, the playfulness of using such a device in a dramatically low-stakes style of story, as well as the clever ambiguity of the chapter’s titles, add an element of fun and humour to the novel, encouraging us to maintain a somewhat detached perspective, and thereby enabling us more clearly to understand the ironical nature of much of the story.

This playfulness carries over into the way mythology, premonition, and spirituality are incorporated into the story, and so it seems fitting that we should begin our exploration by discussing the ways that the supernatural and the dream-like manifest within the novel.

DREAM WORLDS

Dream of the Red Chamber begins far away from the Jia household in which we will be spending most of our time. After a quick introduction by the author, we are presented with a small fable that explains where the story came from. We are told that when the Goddess Nu Wa melted down rocks to repair the sky, she made 36,501 stones, each 120 feet high and 240 feet square. However, she ended up using only 36,500 of these stones, and threw the remaining one down at the foot of a mountain. This stone had somehow during this process acquired spiritual understanding, and therefore spent many a long year lamenting the fact that it had not been chosen to mend the sky.

After a while, a Taoist priest and a Buddhist monk show up, and find that the Stone had in the meantime shrunk to the point where it can fit in the palm of someone’s hand. The monk recognizes that this Stone is precious, but that it has as yet no real value, and decides to take it to a cultured family and allow it to see some of the world while living in comfort.

Many generations or aeons later, another Taoist known as Reverend Void comes across the Stone, once again at the foot of this same mountain. He finds inscribed on the back of the Stone the complete story of the Stone’s experiences on Earth. After a brief conversation regarding the merits and flaws of the tale, reflecting the ways in which it differs from more conventional stories, primarily in its realism and lack of stereotype, the monk is persuaded to re-read and reconsider the story, and is won over by its quality. He decides to publish the book, which ends up being this book, the Dream of the Red Chamber.

We are then introduced to Zhen Shih-yin, who has a dream in which he sees the Buddhist monk and Taoist priest right after they’ve picked up the Stone originally. The monk explains to the Priest: “a love drama is about to be enacted, but not all its actors have yet been incarnated. I’m going to slip this silly thing in among them to give it the experience it wants.”

He goes on to tell the story of a Vermillion Pearl Plant growing on the bank of the Sacred River, which was watered every day by a man named Shen Ying, an attendant in the Palace of Red Jade. Eventually, this Vermillion Pearl Plant, after being watered by the essences of Heaven and Earth, transformed into a human girl. As a human girl, she roamed “beyond the Sphere of Parting Sorrow” and drank from the Sea of Brimming Grief. She had no way of repaying the kindness of Shen Ying, and this made her heart heavy indeed.

As luck would have it, Shen Ying is seized by a sudden desire to become a human himself and visit the human world. He asks the Goddess of Disenchantment to allow him to do so, and she sees this opportunity to allow Vermillion Pearl Plant to repay her debt of gratitude. She wants to “repay him with as many tears as I can shed in a lifetime.” Along with her, many other amorous spirits who have never atoned for their sins decided to accompany the two of them, and play their own part in the oncoming drama.

After overhearing this conversation between the monk and the priest, Zhen Shih-yin, who is seeing this all in a dream, asks them to explain the mystery of what they’re talking about. They show him the Stone, which is now a piece of translucent jade called the Jade of Spiritual Understanding.

The dream ends when they reach the Illusory Land of Great Void, whereupon there are two pillars inscribed with a couplet that reads:

When false is taken for true, true becomes false;

If non-being turns into being, being becomes non-being.

This couplet is deliberately nonsensical, even in Chinese. In the vein of the Tao Te Ching or the Chuang Tzu, it plays with contradiction and ambiguity in an attempt to get at truths that are immediately unintuitive. This theme of truth and falsehood plays a subtle role in the novel. I’ve already mentioned in the introduction the contrast between form and reality that plays a large role in the novel, but that is only one aspect of what’s going on here.

Jia Baoyu, the main character of the novel, is born with this Jade of Spiritual Understanding in his mouth, and his name Baoyu means “precious jade.” He lives among the so-called “Twelve Beauties of Jinling,” a name for a dozen of the more important women in the novel, who are the reincarnated spirits mentioned earlier.

The family name Jia is a homophone of the word “false” or “fictitious,” and during a conversation at the beginning of the novel, they are directly compared to another family named Zhen, a homophone for “true.” Thus, the family name Jia, or falsehood, is a reflection of the contrast between the material world and the heavenly, spiritual world. These characters don’t really belong here in the human world; their real forms are the heavenly spirits from which they have been transformed, and to which form they will return after their death.

Unlike other stories where dreams are subordinate to the real world, either as manifestations of psychic states, or simply wild fantasies, in this book it is the real world, the material world, that is fake, and the heavenly realm that is real. This is concordant with Buddhist and Taoist metaphysics, but I don’t believe the novel is being precisely literal by invoking these concepts; I think that it uses them as a framework for understanding the characters and the social conditions found in the book.

Latching onto the idea that the world is fake is often a symptom of dissatisfaction with the state of things, either on a personal, social or a political level. If things were going well down here, what use would there be for another world up there? However, it also allows one to forgive people for being, well, people, because it means accepting that there is no such thing as perfection on this Earth. We see both of these aspects at work in this novel.

In a way, Cao Xueqin is playing around with certain characteristics of fiction. He stresses at many points in the introduction the realism of the novel, that these characters are real people, not the sort of stereotypes you’d find in operas or romances. He also stresses the mundanity of the work, somewhat ironically stating that the novel does not have political overtones, and is instead simply a book about a bunch of young girls living in a Garden.

So, the characters are real, in that they resemble real people, and they live the sort of everyday life that real people live. However, at the same time, they are fake; their very name reveals them to be so: they are manifestations of heavenly spirits, and also, in another sense, they are characters in a work of fiction. They are real fake people, and they are fake real people. “When false is taken for true, true becomes false. If non—being turns into being, being becomes non-being.” This contradictory and nonsensical couplet actually, in a strange way, describes exactly what’s happening in the book, and the multiple ways you need to look at it in order to make any sense of it.

While the book is enjoyable in itself without worrying about any of this, the frame-story here adds additional layers of meaning and mystery to the novel, and puts into perspective certain enigmatic scenes that would feel out of place in a strictly realist work.

This interplay of truth and falsehood is what elevates the novel beyond being just a love story, or just a family tragedy. Lying in shadow behind everything is a sort of cosmic structure that adds cohesion to all the disparate events and characters. It’s what prevents the novel from just being a bunch of things that happen to a bunch of people. At the same time, it’s not so straightforward that it feels tacked on or unnecessary. It’s its ambiguity, and the fact that it seemingly disappears into the background for long stretches of time, that makes this frame-story so effective.

BAOYU & HIS DREAMS

The story centres around Jia Baoyu, the young man born with a jade pendant in his mouth. Baoyu is the son of Jia Zheng, the second son of the Lady Dowager and de facto head of the household. Baoyu is his grandmother’s favourite of all her grandchildren, and thus is spoiled, allowing all of his eccentricities to thrive in the almost unreal world of a wealthy elite family. Thus, Baoyu doesn’t put effort into his studies, and instead spends most of his time playing around with his cousins and sisters.

Baoyu is much more comfortable in the company of women than of men. He believes men are dirty and crude, unintelligent and unrefined. Women, on the other hand, are not only beautiful and elegant, but also more clever, and more artistic. In many ways, Baoyu is treated almost the same way as many of his female relatives. It’s only the rare scene in which he hangs out with any of the other boys, and when he does, such as when he tries to go to school, it often ends in conflict.

His male relatives, for the most part, only serve to prove his preconceptions. They are often womanizers or drunks, or else pious to the point of losing touch with reality. Baoyu’s attachment to reality is tenuous at best, and he often speaks complete nonsense, but he is kept down to Earth to a certain extent by his female companions. The women of the family, particularly the third generation with which Baoyu spends most of his time, are able to maintain a balance between Heaven and Earth.

They are, in a way, worldly, in that they understand their position both in the family and in the world. They know that, as women in a male-dominated society, their position is often tenuous at best; even if they marry a wealthy man, there’s always the chance that he may later take a concubine that he fancies more than them. Or else, they might become a concubine themselves; in particular cases, they are orphaned, such that if they lose the generosity that is being accorded to them by the Lady Dowager, they might even become servants.

This understanding of their material position is also what allows them their philosophical and artistic maturity. Some are skilled poets, some skilled artists, and all of them at least have an appreciation for such otherworldly activities. Early in the novel, they create a poetry club, where they get together and compose long or short poems, at which composition they consistently outdo Baoyu, who is supposed to be more learned.

But at the same time, these are teenage girls, and for all their maturity they are also emotional and occasionally cruel. But once again, Baoyu is the most emotional of them all, the most gullible, the most impressionable, and the most naive. It seems that he can not shake this masculine tendency toward extremes; when living almost as a girl, he lives as the most extreme form of girl, because he doesn’t have that worldly understanding of his position. As a man, or as a boy, he is given many privileges and assured of certain things that are not assured to the girls, and this security allows him to embark on flights of fancy that are both ridiculous and destructive.

However, as a sort of untethered emotional machine, Baoyu is immediately relatable, if only as a representation of our most extreme moments. We have all experienced the emotions he undergoes, but we are never allowed to experience them quite at the extent to which he does.

It is important to mention though that Baoyu is also kind and generous, offering help and compliments to all the girls and always looking for ways to cheer them up. He is carefree and doesn’t mind being the butt of jokes or being criticized. In fact, he doesn’t seem to have much care for himself at all, and his only joy in life is the joy of his cousins, sisters and maids. He has a bizarre sort of philosophical bent that makes the tribulations of this world flow by him like water off a duck’s back. This combination of naivete and a sort of wisdom gives him the character of a holy fool, or a Taoist sage.

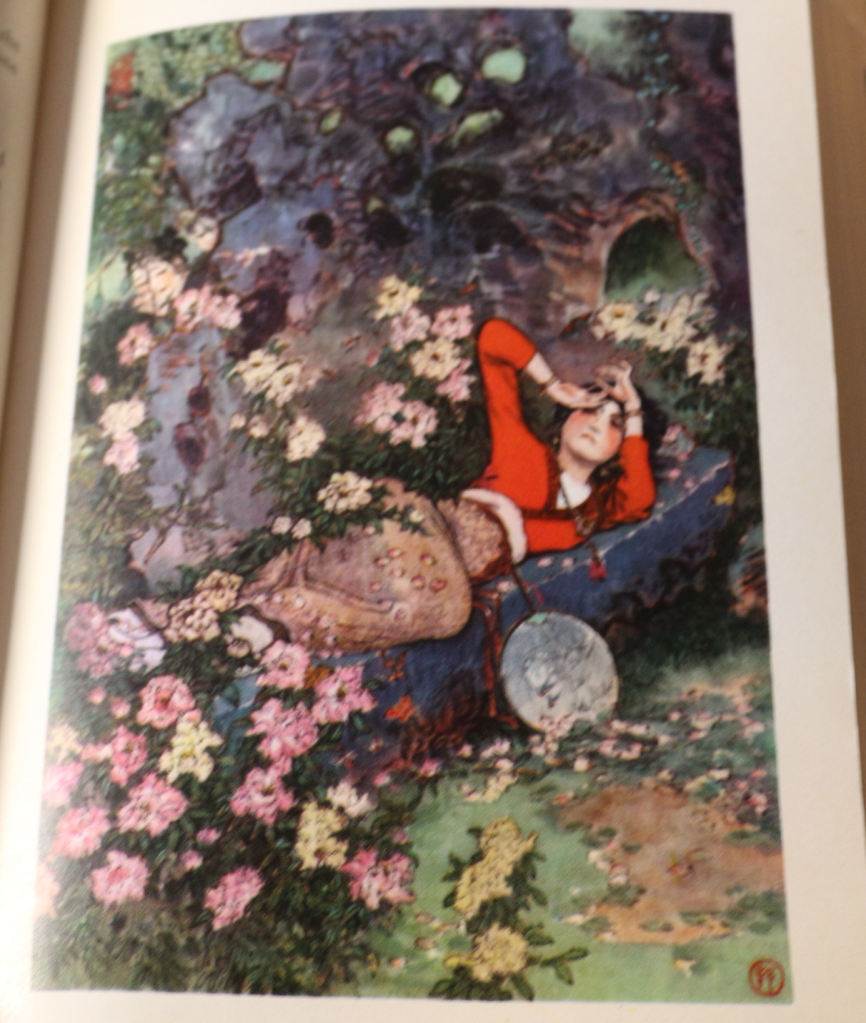

Early in the book, Baoyu and his sisters and female cousins move into a section of the family estate that was originally designed for a visit from his sister, the Imperial Consort. This area is a vast garden, complete with flowing streams, rocky paths, stony hills, and lush verdure. This idyllic realm is where much of the story takes place, with each character living in one of the homes or cottages within the garden. They travel to other sections of the estate in order to visit their older relatives, but for the most part, they are secluded within this world.

But even when they do travel outside, it’s mostly to visit their mothers, aunts or grandmother. It’s important to emphasize that outside of Baoyu, there is very little male presence in this book, and when they do show up, it’s often disastrous. Baoyu’s relationship to his father, Jia Zheng, is incredibly strained, as Zheng sees Baoyu as an eccentric bumbler and a total disappointment. He views Baoyu’s tendency toward femininity as a sort of perversion, as if Baoyu is a lecherous young man who is drawn to girls purely out of lust. At a certain point, he believes a rumour spread by Baoyu’s jealous half-brother about Baoyu attempting to rape a maid. This, combined with another rumour about Baoyu engaging in homosexual acts with an actor from another household, causes Jia Zheng to beat Baoyu almost to death.

The fact that these rumours are both untrue is less important than the fact that Zheng believes them to be true. In his eyes, Baoyu is a sexual deviant, a result of the complete lack of control anyone has over him. Because Baoyu is the Lady Dowager’s favourite, and Zheng has to comply with her wishes being her son, Zheng feels that he has not been able to raise Baoyu properly. Zheng believes in a Confucian ideal of society, where the highest values are pious respect for male relatives, and faithful service to the government, with both of these being intertwined in a sort of paternalistic complex. If Zheng had his way, Baoyu would spend all his time studying the Four Books and Five Classics which are the staples of a Confucian education.

One can almost understand Zheng’s concern here, as when considered practically, Baoyu’s situation and education is pretty poor. However, practicality is exactly the sort of thing Baoyu rejects. Baoyu almost floats above the world, and explicitly doesn’t belong in it. Trying to impose practicality or pragmatism on such a being is impossible, and in many ways might only make him worse off.

But it’s perhaps worthwhile to try to understand what role the lust that Zheng perceives in Baoyu’s actions actually plays. While the book is often tame or indirect in its depictions of sexuality, it does not try to ignore its existence. As in many cultures, sexuality is rarely explicitly mentioned within the Jia household, and when it does appear in the novel, it is often as something hidden being stumbled upon by one of the primary characters. These scenes imply that sexuality almost exists as a sort of shadow world behind the clean and respectable surface.

The most explicit and enigmatic nod to Baoyu’s sexuality in the novel occurs near the beginning, during the eponymous Dream of the Red Chamber, dreamt by Baoyu during a visit to his family in the Ning household across the street. The Ning household, of which Jia Zhen is the head (not to be confused with Jia Zheng with a g, who is Baoyu’s father), are distantly related to Baoyu’s family from his grandmother’s generation, with Jia Zhen being a sort of distant-cousin sort of relation.

When Baoyu is overtaken by sleepiness during his visit, Qin Keqing, who is Zhen’s daughter-in-law, and importantly not related to Baoyu in any meaningful sense, arranges for Baoyu to have a nap somewhere. However, the first room she tries to set him up in has a couplet on the wall that reads,

A grasp of mundane affairs is genuine knowledge

Understanding of worldly wisdom is true learning.

Baoyu is so disgusted by this sentiment that he refuses to sleep in the room, so Qin Keqing takes him to her own chamber. Qin Keqing’s room is filled with the aroma of perfume, and adorned with artifacts belonging to sensual women from history and myth. Qin Keqing here is an embodiment of sexuality, and by taking Baoyu to her chamber she is initiating him to this semi-secret sort of realm. When Baoyu falls asleep, he is led by a dream-version of Qin Keqing into a pleasant land, where he meets a fairy that turns out to be the Goddess of Disenchantment, whom we met in the initial frame-story.

Here, the Goddess shows Baoyu to an area where he opens a cabinet and finds the “Register of the Twelve Beauties of Jinling,” which contains descriptions of the fates of many of the characters; however, written in such a way and introduced at such a point in the story that it’s impossible for either Baoyu or the reader to make much sense of them. She also orders some maids to sing Baoyu a collection of songs called the “Dream of the Red Chamber,” which similarly foreshadow future events, and introduce the thematic qualities of the main characters, once again without explicitly naming the characters in question.

Baoyu soon grows bored of these mysterious songs, and wishes to sleep in his dream. The Goddess of Disenchantment leads him to a chamber, where she speaks to him about the error of treating love and lust as two disparate things. “Love of beauty leads to lust,” she says, “Thus, every sexual transport of cloud and rain is the inevitable climax of love of beauty and desire.”

“And what I like about you,” she says to Baoyu, “is that you are the most lustful man ever to have lived in this world since time immemorial.”

Frightened by this assertion, Baoyu pleads innocence. His parents already admonish him enough for his laziness, to add lustfulness to that would simply be too much. Besides, he says, he’s still too young to really understand what lust is.

The Goddess explains that Baoyu’s lust is not the lust of people who crave physical pleasure, but is instead “lust of the mind.” It can not be expressed physically, but only apprehended intuitively. She says that this is what makes him such a welcome companion to women, but also what makes him seem odd in the eyes of the world.

In order to prove to Baoyu the illusory nature of physical desire, she introduces Baoyu to a girl she describes as her younger sister. This girl is named Chien-mei, which means, “Combining the best,” the meaning of which I will get into into a little bit later. For the moment, we can say that the Goddess hopes that after they “consummate their union” Baoyu will see the vanity and emptiness of sex, even in this heavenly realm. She hopes to cure him of his lustful nature, so that he will be able to devote himself instead to the betterment of society. As the narrator says, “We can draw a veil over this first act of love.”

Unfortunately, Baoyu becomes attached, in the dream, to this younger sister, whose name is now suddenly Ko-ching, in the way that dream figures often change their names or even change into other people completely. Baoyu and Ko-ching go for a stroll, and find themselves in a dense forest, before a rushing river. The Goddess of Disenchantment finds them there, and she tells them that this is the Ford of Infatuation, and that if they had fallen in, all her work would have been for naught.

Monsters and devils emerge from the river. Frightened, Baoyu screams out, and this scream escapes into the real world and wakes him up. His head maid Xiren, finds that he has ejaculated in his dream. Later that night, he tells her of the nature of the dream, and all that happened to him. Xiren, a few years older than Baoyu, finds the entire thing hilarious, no doubt considering it the wild fantasy of a sexually frustrated young boy. They secretly have sex, and we are told that “from that hour, Baoyu treated Xiren with special consideration.”

One might pause to wonder here if the Goddess was successful or unsuccessful in her gambit. When the real world mirrors the dream world, i.e. when Baoyu follows his first act of love in the fairyland with his first act of love in the material world, we have to wonder if this mirroring is a part of the lesson he is supposed to learn, or if it is proof that it has not been learned, and that he instead has only increased his lustiness and thereby his attachment to material pleasures. When we’re told that the relationship between Xiren and Baoyu is strengthened by this event, it parallels Baoyu’s strengthened relationship with the dream girl that leads him to the terrifying Ford of Infatuation.

However, maybe we should remind ourselves of the couplet again:

When false is taken for true, true becomes false;

If non-being turns into being, being becomes non-being.

If we consider the non-being or false to be Baoyu’s encounter with Chien-mei in the dream, and the true or being to be Baoyu’s real-life encounter with Xiren, we have to consider that this would then cause the true or being to become false or non-being. Which we could take to mean that Baoyu’s lust, by this action, has been nullified, in a sense, has been made unreal or untrue, and therefore no longer a real problem. This reading is somewhat vindicated by the fact that, during the rest of the novel, we don’t see Baoyu acting out on any sexual urges, although his “lust of the mind” is just as powerful as ever.

DAIYU & BAOCHAI

This ambiguity is only made more mysterious when we consider this dream girl’s name, Chien-mei, “Combining the best.” This name is a reference to Baoyu’s two “love interests,” I guess you could say, whose complementary natures and differing relationships with Baoyu are at the heart of the novel.

Lin Dai-yu, whose name means “black jade,” and Xue Baochai, whose name means “jewel hair-pin,” are two of Baoyu’s cousins who live with him in the garden.

Lin Dai-yu is the daughter of Baoyu’s paternal aunt, who married a scholar and moved away from the family. When Dai-yu’s mother dies, her father sends her to live in the Jia household for a time, and it is through Dai-yu’s eyes that we as the reader first experience the mansions. Soon after, her father also passes away, leaving her an orphan under the care of her grandmother, the Lady Dowager. As such, she is a melancholy child, lamenting the loss of her parents and full of guilt for being a strain on her extended family.

A pageboy in Chapter 65, speaking behind her back, describes Dai-yu as having “a bellyful of book learning…; but she’s always falling ill. Even in hot weather… she wears lined clothes, and a puff of wind can blow her over. Being a disrespectful lot, we all call her the Sick Beauty.”

Baoyu and Dai-yu have a special bond; when Dai-yu first visits the mansion and sees Baoyu, she finds him familiar, as if she’s seen him somewhere before. Baoyu, in turn, studies her, and declares to his family; “I’ve met this cousin before.” His grandmother insists that he most assuredly has not. He replies, “Well, even if I haven’t, her face looks familiar. I feel we’re old friends meeting again after a long separation.” This is, of course, because they are the reincarnations of Shen Ying and the Vermillion Pearl Plant, and Daiyu is here to repay her debt with tears.

Thus, despite their initial affinity, Baoyu and Dai-yu’s relationship is never without its rockiness. Both being extremely emotional individuals, they push each other away even as they grow closer, constantly irritating and angering each other with misplaced words and deliberate misunderstandings.

Daiyu is sensitive, to say the least, about her familial situation. Anything that reminds her of her parents or her home, or the precariousness of her situation in the Jia household can send her into fits of tears. Often, she hears only what she wants to hear, transforming innocuous remarks into extremely subtle digs at her insecurities. On top of this, Daiyu very rarely says what she means, or conveys in any way the real reasons behind her emotional outbursts, often trying to cover them up with fake reasons, even though everyone around her can clearly tell that she’s lying. Baoyu, being a careless young man with a propensity for talking nonsense, often finds himself in the doghouse. Many of their meetings end with both of them in tears, either tears of mutual sympathy or tears of anger and frustration.

But despite all this, they remain loyal to each other, and their fights rarely last long. Baoyu takes special care of Daiyu, procuring extra medicine during her illnesses, or ensuring the daily delivery of a special soup she likes. And whenever he sees her in tears, he does everything he can to cheer her up, often insisting that he’d rather die than see her sad. “If I meant to insult you,” he says at one point, “I’ll fall into the pond tomorrow and let the scabby-headed tortoise swallow me, so that I change into a big turtle myself. Then when you become a lady of the first rank and go at last to your paradise in the West, I shall bear the stone tablet at your grave on my back for ever.”

It is an open secret within the household that Baoyu and Daiyu will get married when they’re older. It’s clear to everyone how much they care for each other, and both being favourites of their grandmother, there’s no way anyone could object. The only people for whom its not a sure thing are Baoyu and Daiyu themselves. Any reference, either joking or serious, to Daiyu getting married at any point in the future sends her into a fit of rage, as she believes people are making fun of her. It seems that, although she understands Baoyu’s love for her, she doesn’t want to get her hopes up after all the loss she’s suffered in her young life. It’s a case of deliberately not seeing what’s in front of her, for fear that what she sees might be an illusion.

This insecurity, in both senses of the word, is a key part of her tragic nature. She doesn’t feel safe or at home in the Jia household; being a daughter of a daughter, rather than a daughter of a son, their formal responsibilities to her are much less than to the other girls. While the Lady Dowager assures that she is treated exactly the same as her other granddaughters, this informal understanding has no legal or traditional basis, and is entirely tied to the whim of the Lady Dowager herself. If she were to die, or change her mind, then there’s no reason why they couldn’t marry her off or simply send her somewhere else. This ambiguity between her formal position and informal position is a key aspect of her emotional instability.

Baoyu, being the heir apparent to the household, knows nothing but total security, as everyone adheres to his whims and seemingly always will. Thus, he fails to understand Daiyu’s situation, and when it is finally made clear to him, he suffers a complete breakdown. But, perhaps we will talk more about that some other time.

For now, let’s turn to Xue Baochai. Xue Baochai is the daughter of Aunt Xue, Baoyu’s maternal aunt. Like Daiyu, she is a traditional beauty who is also well-educated. The two of them are always quick to quote a passage from an ancient text, and are two of the most accomplished poets among the family. However, in every other way, they are quite different.

Baochai’s father is dead and her brother Xue Pan is good for nothing. She has to give up her education at an early age in order to help her mother with the household, and thereby grows into quite a capable young woman. When her brother decides to take the family to the capital, Baochai and her mother convince him to stay with their extended family in the Jia household, partially to keep him from being completely free to ruin himself.

Baochai is considerate and tactful, always generous and accommodating to her maids. She is not this way necessarily by nature; it is a conscious decision that she makes, understanding the consequences that can come from offending people. She is much more mature than Daiyu, in the sense that she is much more worldly. She understands her position, understands the consequences of certain actions, and acts logically and reasonably.

Daiyu, on the other hand, is, similarly to Baoyu, immature. She sees everything emotionally, and this makes her self-centred and aloof. For all the worrying she does about what the family thinks of her, she still often speaks in a harsh manner that can rub people the wrong way, or makes childish scenes for no real reason. In this book, many physical illnesses are not caused by disease necessarily, but by emotional states. People’s humours get out of line by crying too much, or they get so angry or sad that they throw up. Thus, we can say that Daiyu’s emotional instability contributes directly to her sickliness.

When Baochai initially moves into the mansion, Daiyu is jealous. She thinks that with Baochai around, not only Baoyu but also the Lady Dowager might forget about her, and her privileged position in the mansions might fade away. She sees all the ways in which Baochai exceeds her: in learning, in manners, in propriety, maturity, and in generosity.

But, as is often the case when it comes to people with such contrasting natures, the two eventually become close friends. The circumstances surrounding this are somewhat interesting. Daiyu, while walking in the garden, comes across Baoyu reading a book by a stream. This book is Romance of the Western Chamber, a romantic drama generally considered indecent and immoral at the time, due to its two principal characters consummating their love without parental approval. Baoyu is crazy about the book, because of course he would be, and he lends it to Daiyu, who is also entranced by it.

In Chapter 40, Daiyu, who has in the meantime memorized the entire play, accidentally quotes a line from it during a drinking game. No one else notices, aside from Baochai, who a few chapters later, in a chapter titled “The Lady of the Alpinia Warns Against Dubious Tastes in Literature,” takes Daiyu aside and questions her about her reading habits. She reveals that she has also read these books, back when she was a “madcap” and “a real handful.” But she goes on to say,

“It’s best for girls like us to not know how to read… If boys learn sound principles by studying so that they can help the government… well and good; but nowadays we don’t hear of many such cases — reading only seems to make them worse than they were to start with… As for us, we should just stick to needlework… If we let ourselves be influenced by those unorthodox books, there’s no hope for us.”

Considering the context, this is obviously meant to be read as irony. There’s a common theme to this novel about how it’s unlike any other story: both licentious dramas and more approved works with explicit moral themes. This kind of blanket moral statement regarding fiction is exactly what Cao Xueqin is fighting against.

However, Daiyu is impressed by Baochai’s reasonableness, as well as her care in taking the time to warn Daiyu. It’s clear that Baochai is not making a statement about the quality of these works, as much as a statement about their reputation, and about how reading them will affect one’s status, rather than one’s mind. It’s a material analysis, a grounded view of social reality, which flies in the face of Daiyu and Baoyu’s idealistic appreciation of the stories simply as stories. In this moment of hearing Baochai lecture about stories, Daiyu grows up a bit — or at least, begins to see what it means to be a grown up.

This contrast between materialism and idealism is further symbolized by Baochai’s golden locket. She was given an inscription for this locket by a Buddhist monk when she was a child, which inscription seems to complement the inscription on Baoyu’s Jade of Spiritual Understanding. This adds a complication to this triangle, because as readers, we know that Baoyu and Daiyu are connected via their former relationship as Shen Ying and the Vermillion Pearl Plant. However, to other characters in the novel, Baoyu and Baochai seem to be destined for each other due to their complementary accessories. This is another case of confusion between illusion and reality, with material reality itself being the illusion, and true reality being something hidden that no one can possibly know about.

Thus, the question of whether Baoyu should or will marry either Daiyu or Baochai is a question of which way of viewing reality takes precedence. From a pragmatic point of view, Baochai makes the most sense. She can act as a foil to Baoyu’s absurd ways, and she is capable of running a household. However, from a romantic point of view, the love between Baoyu and Daiyu is clearly stronger. Her sickliness, combined with the fact that their emotional natures only make each other more and more crazy, meaning that their household and their life would be complete chaos, makes love seems ill-fated for our world. It’s a heavenly love, a love from another dimension, and this is what makes it beautiful, and perhaps what also makes it impossible.

As readers, we can see both sides of this dilemma, and, if we allow ourselves, we can even sympathize with both. Our impractical and emotional side will always lean toward Daiyu; our pragmatic side will always lean toward Baochai. If we empathize with Baoyu, we want what’s best for him: but it’s almost impossible to truly understand what is actually best. Is Baoyu’s father’s practical Confucianism the proper outlook on life, or is the enlightened foolishness of Taoism or Buddhism really the better way to go? As always, Cao Xueqin does not provide us with a real answer: both sides are made to seem superior or inferior in turn. We see characters in the book turn away from society and embrace Taoism, but we never see what actually becomes of them, and it’s hard to know if it matters what becomes of them, because they are explicitly rejecting their physical presence on Earth.

We return to this question of what is real in the story. Is the story of the characters in the Jia household what is real, or is it the frame-story regarding the stone and the heavenly realm that is real? Or are neither of them real, or are both of them real? True becomes false, being becomes non-being; perhaps these boundaries are less strict than they initially seem. There’s permeability between these realms; spirits become human, and humans become spirits. If this interchange is always re-occurring, then who is to say which side is the real side and which side is the unreal side?

I suppose we’ll just have to read on, and find out.

CONCLUSION

In the next Part of my series about Dream of the Red Chamber, I will zoom out a bit from Baoyu and Daiyu and Baochai, and discuss many of the other members of the Jia family. We will explore the perspectives of older characters and of characters from different backgrounds, and see how these all fit into the tapestry of the novel. If this book were only about Baoyu, Daiyu, and Baochai, it would be a romance; but this book is decidedly more than just a romance. There’s much more to the story: themes regarding the nature of nobility and wealth; of ritual and form; as well there are playful moments, beautiful moments, and tragic moments. While I can’t possibly cover everything that goes on, I will attempt in the next part to provide you with something of an overview. Following that, there will be a third part, in which I cover the final section of the book, where we find out the fates of our beloved characters, and try to figure out what exactly it is that we take away from reading this novel.